ON SUNDAY JULY 20, 1924, 12,000 spectators—the men in bowler hats, the buttoned-up women twirling parasols—crept forward at Paris’ sold-out, swelteringly hot Piscine des Tourelles outdoor stadium, waiting on the upraised starter’s gun. Hollywood’s Doug Fairbanks Jr., and Mary Pickford, and famous sprinter Charlie Paddock, just dethroned as the world’s fastest man, sat in lower boxes, hoping their old friend had one more miracle in him. In one of the last events in a sprawling and spotty three-weeks-long 8th Olympiad, the august French Olympic Games director Count Clary was unmissable with his wizard length white beard. The Games architect, the diminutive and often melancholic Baron Pierre de Coubertin, sat delighted by the arena’s positive energy. Italian fascist displays and spectator riots tainted the previous weeks, but this was golden, each customer a part of something greater. It was like a first-order Fresnel lens, bending many points of light into a singular beam so strong and luminous it could cut through the darkness of a stormy sea.

All had turned out despite an ongoing heat wave that scorched the city that day with 100-degree temperatures. On tap was the long awaited 100-meter swimming showdown between Chicago’s brash world record holder Johnny Weissmuller and Hawaii’s stoic Duke Kahanamoku, the two-time defending Olympic sprint champ.

The two stood poised for the first time ever in adjacent middle lanes on the edge of the pool deck, the 50-meter sheet of water in front of them separated by strands of floating cork, a simple but crucial innovation to prevent the oft-happening chaos of exhausted or spiteful racers thrashing into one another. Boilers installed only weeks earlier heated the water to a race-optimum 70 degrees.

Crouched in their knee-bent forward stances, their arms retracted behind them like airplane wings, Duke and Johnny were strikingly handsome. In their chiseled, 6-foot-plus frames, their pectoral and shoulder muscles outlined in form fitting one piece bathing suits, each was hard to keep eyes off of. They were the glistening homo erotic illustrations of J.C. Leyendecker come to life. Coming out of era where leisure-seeking beach goers often lay in the hot white sand in full dark suits, their female companions safely segregated behind ropes on separate beaches, Duke, and now Johnny, looked the way a young man ached to look: physical and free and desirable.

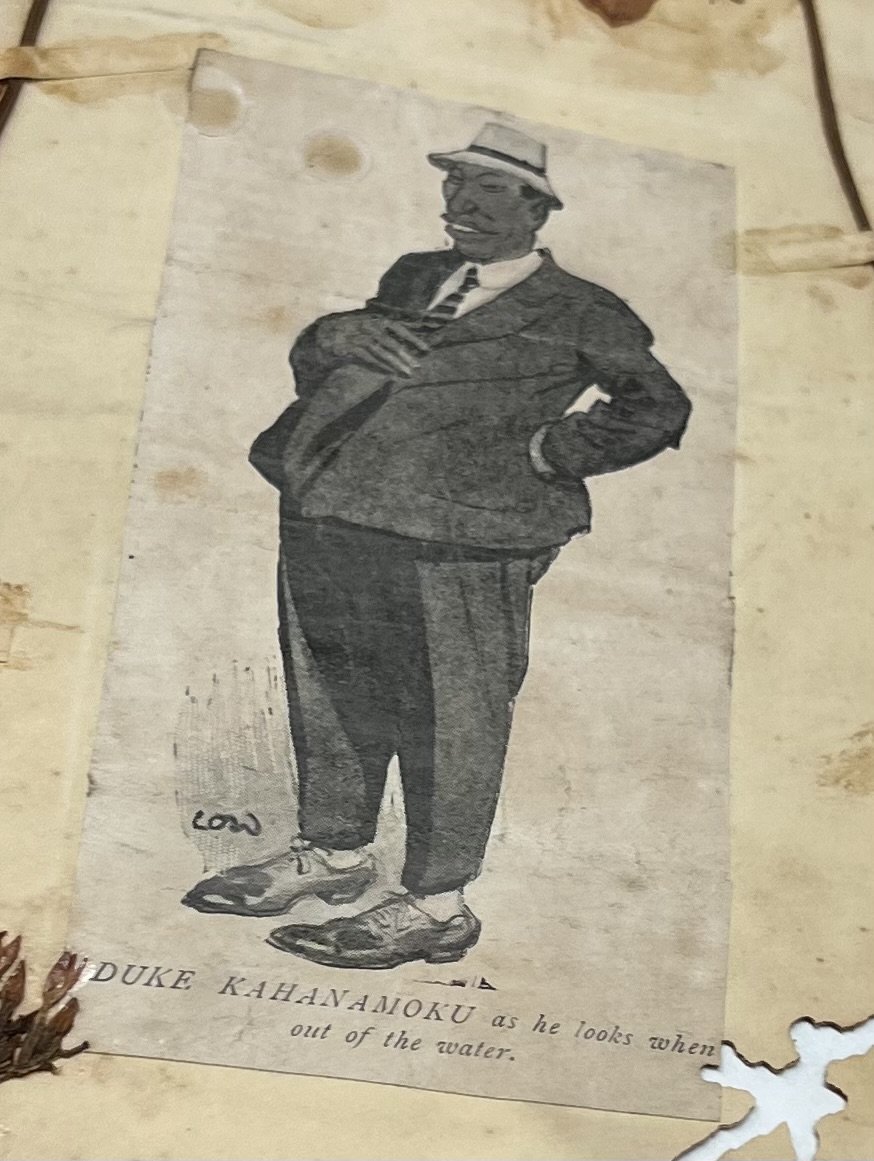

Racist cartoon about Duke Kahanamoku during his tour of Australia in 1916. Credit: Bishop Museum

Drawing of the Tourelles swimming stadium in Paris

Newlywed celebs Katsuo Takaishi and Mineko Takaishi after their marriage in 1933. Credit: Courtesy of Takaishi family

Takaishi and Weissmuller in Tokyo

Katsuo Takaishi

Portrait of the Japanese swimming team taken in the Olympic village in Paris. Sitting from right is the master coach Den Sugimoto

Weissmuller shaking the hand of his Japanese rival Katsuo Takaishi

Life magazine Olympic edition in July 1924

Duke and Johnny in an impromptu hula dance at a 1950 Hall of Fame ceremony in LA. Credit: Bishop Museum

Young Johnny Weissmuller. Credit: Chicago History Museum

Katsuo Takaishi in a mid 1920s visit to Hawaii

Johnny posing for his portrait at the Pach Brothers studio in New York City in 1924. Credit: National Portrait Gallery

Duke on the running board and rival IAC coach Bill Bachrach during a meet in Hawaii in 1919. Credit: Bishop Museum

Duke teaching actress Laura Anson the crawl stroke in a 1922 Hollywood film

Caricature of Johnny and the Kahanamoku brothers published in the Parisian paper, Le Miroir des Sports, during the 1924 Olympics

Duke and the triumphant 1920 American Olympic team marching down 5th Avenue in Manhattan. Credit: Library of Congress